Chasing Paradise: De Profundis and the True Artist

In the finale of our Chasing Paradise column we follow Oscar Wilde’s last epiphanies, and get a glimpse of how Paradise might after all be chased successfully.

Abigail Leali / MutualArt

Dec 09, 2022

In 1895, Oscar Wilde was imprisoned after a chaotic and scandalous libel trial that resulted in a maximum sentence of hard labor for gross indecency with men. The grueling struggle of prison life quickly threw a bucket of freezing water on his raucous, decadent lifestyle. He had come to a fork in the road: lean into his hedonistic tendencies and find himself more and more embittered by his altered circumstances, or change his approach altogether to account for this new, bleak way of life.

Wilde rarely did anything by halves. Somehow, he managed to take both roads. In De Profundis, his 1897 letter to “Bosie” or Lord Alfred Douglas (whose relationship with Wilde had sparked the entire messy affair), he does not shy away from recalling Bosie’s faults or his own weaknesses. And yet, he also acknowledges that even though he cannot bring himself to regret his previous life of pleasure, “the other half of the garden [has] its secrets for me also.”

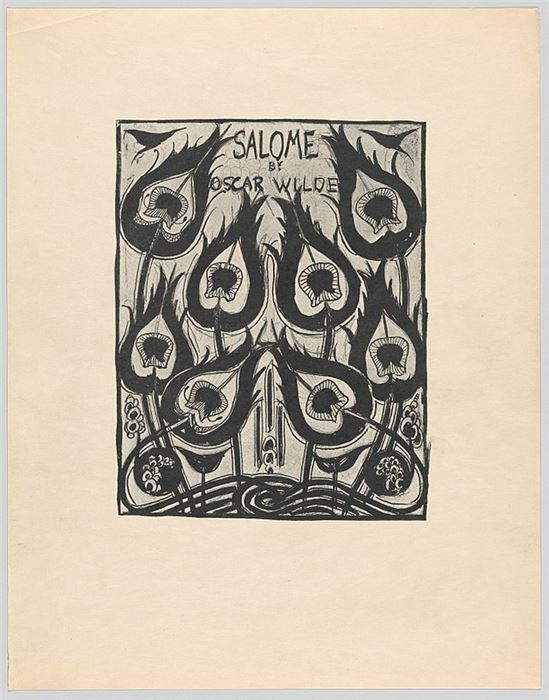

Aubrey Beardsley, cover of Salomé, c. 1894

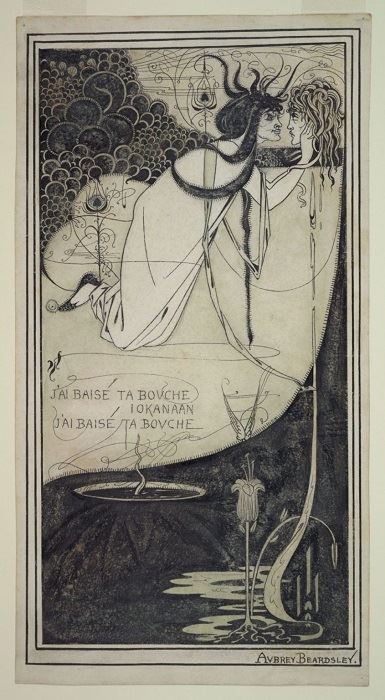

Wilde had already spent several decades in the Japonesque garden of The Picture of Dorian Gray. Like Dorian, he had pursued pleasure recklessly, even to his own destruction. But he admits that this “other half of the garden” had long lingered in the back of his mind. It manifested as “the note of doom that like a purple thread [ran] through the texture of Dorian Gray.” It was also the menacing cloud over his play Salomé, influencing Aubrey Beardsley’s stark illustrations with its mangled depiction of innocence and virtue encountering greed, lust, and deceit.

For Wilde, the lavish luxuries of ukiyo-e were a perfect metonymy for Decadence as a whole, defining it as a radical alternative to traditional Western norms – a world of guiltless parties, drinking, drugs, and sex. Enticing as this prospect may have been, Wilde had begun to realize that it was these very vices that had dragged him into bickering, into scandals, into metaphysical dread, and ultimately into a cell. Fittingly, in De Profundis he engages more explicitly than ever with this second, hidden interlocutor: asceticism, especially as found in the Catholic Church.

Many take it as a foregone conclusion that Wilde must have raged against the Puritanical society of his day. In one sense, he did. He despised the Victorians’ hypocritical judgments and all but refused to acknowledge them. But it would be false to say he dismissed Christianity itself. Quite the opposite. Throughout the entirety of De Profundis, Wilde praises Christ in the highest terms he can muster: He deems Christ a true artist.

“I see a far more intimate and immediate connection between the true life of Christ and the true life of the artist,” he writes. “[He] who would lead a Christ-like life must be entirely and absolutely himself.” In contrast with the nihilism he saw in ukiyo-e, Wilde discovered that the life of Christ embodied what he found so life-giving about art: the ability to cut to the heart of reality, to see each person, place, and thing as it truly was. Yet what did it mean to be oneself?

Aubrey Beardsley, original design of Salomé with the Head of John the Baptist, c. 1894

“Truth in art,” he goes on, “is the unity of a thing with itself: the outward rendered expressive of the inward: the soul made incarnate: the body instinct with spirit.” The artist’s role, in other words, is to bring each thing’s internal existence in harmony with its external reality. As we might put it today, it is to discover its most “authentic” nature. To “be oneself” is thus to live not only according to one’s own desires but also in consideration of one’s relationships and circumstances. The artist, by unifying these aspects, creates “truth in art.”

This conclusion leads Wilde to declare, rather shockingly, “Christ is the most supreme of individualists”:

Humility, like the artistic acceptance of all experience, is merely a mode of manifestation. It is man’s soul that Christ is always looking for. He calls it ‘God’s Kingdom,’ and finds it in every one. He compares it to little things, to a tiny seed, to a handful of leaven, to a pearl. That is because one realizes one’s soul only by getting rid of all alien passions, all acquired culture, and all external possessions, be they good or evil.

When Wilde refers to “humility,” he does not mean it in the modern sense of self-abasement. Rather, he uses it in its original sense: it is the virtue that allows one to see everything (including oneself) as it really is. Whereas Japanese ukiyo-e artists attempted to escape reality, creating a false world in which pleasure could endlessly buffer a person from pain, Wilde’s “true artist” instead faces the world head-on, acknowledging pleasure and pain with equal honesty and rigor.

“For this reason,” he adds, “there is no truth comparable to sorrow.” As alluring as a life of willful escapism may have seemed, paradise cannot be superficial; it must be aligned with the real. The same Wilde who had spent most of his adult years dressing in foppish outfits and carousing, at the end of his life came to realize that asceticism, too, had its place. By eschewing certain pleasures, one could experience truth in a less encumbered way. To always escape pain is to never encounter oneself. To fulfill all one’s wildest fantasies is never to face one’s insecurities, loneliness, and fears.

The ascetic path is, of course, directly opposed to that of decadence and ukiyo-e. That said, Wilde is also clear in De Profundis that the West had lost sight of its own cultural tradition:

…one of the things in history the most to be regretted is that the Christ’s own renaissance, which has produced the Cathedral at Chartres, the Arthurian cycle of legends, the life of St. Francis of Assisi, the art of Giotto, and Dante’s Divine Comedy, was not allowed to develop on its own lines, but was interrupted and spoiled by the dreary classical Renaissance that gave us Petrarch, and Raphael’s frescoes, and Palladian architecture, and formal French tragedy, and St. Paul’s Cathedral, and Pope’s poetry, and everything that is made from without and by dead rules, and does not spring from within through some spirit informing it. But wherever there is a romantic movement in art there somehow, and under some form, is Christ, or the soul of Christ.

Choir, Chartres Cathedral, c. 1134-1260 (photo by Marianne Casamance)

The laissez-faire attitude of ukiyo-e, in other words, was only half of the problem. The Romantic streak in Wilde rejected any superimposed framework that hindered the organic growth of the Western tradition. The West had failed – if not by fleeing reality, then by trying too fiercely to control it.

The solution? Again, art. “Art is a symbol,” he asserts, “because man is a symbol.” Just as the artist gently coaxes an object’s likeness out of the end of a brush, so man must learn to discern and express truth – both the truth of himself and the truth of the world around him.

It is a harder way, to be sure, than that of l’Art pour l’Art. Art is not for its own sake; rather, the journey of artistic encounter is a symbol of the journey each one of us must take to become more fully ourselves. It is a daunting path, threading the needle between aestheticism and asceticism. It is uncharted territory for everyone who traverses it. But for Wilde, it was the only way to regain his individuality in the face of self-annihilating pleasure.

This revelation is perhaps why, despite his qualms about the “dead rules” of the high Renaissance, Wilde ended his life as a deathbed convert to Catholicism. To a casual observer, the move may have seemed like a last-ditch effort to protect himself from the possibility of eternal damnation. But that would not do justice to the depth and nuance of his thought – nor to his lifelong desire to be the most authentic representation of himself.

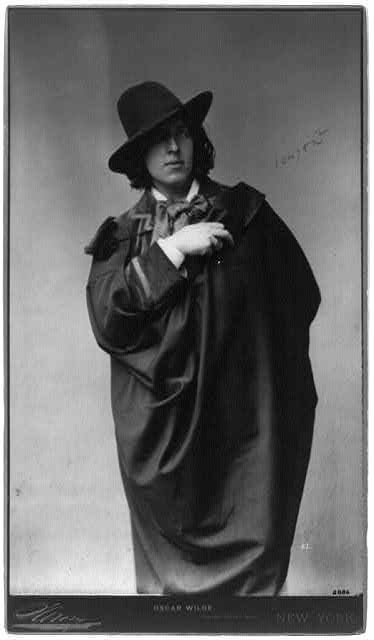

Napoleon Sarony, Oscar Wilde, c. 1882

It would be fairer instead to see in Wilde’s conversion to Catholicism the culmination of a process that had begun all the way back in his college days, when, at the same time as he had immersed himself in the debaucheries of nineteenth-century Oxford collegiate life, he had papered his dorm walls with posters of John Henry Cardinal Newman and planned a trip to Rome. In his conversion, Wilde acknowledged in death a goal he could never achieve in life: to be fully and freely himself, a slave neither to pleasure nor pain. In his final moments, as he embraced this via media, we can hope that he may have at last tasted paradise.

For more on auctions, exhibitions, and current trends, visit our Magazine Page

.Jpeg)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.